Reloj

jueves, 2 de agosto de 2018

Construcción de una levadura con un único cromosoma

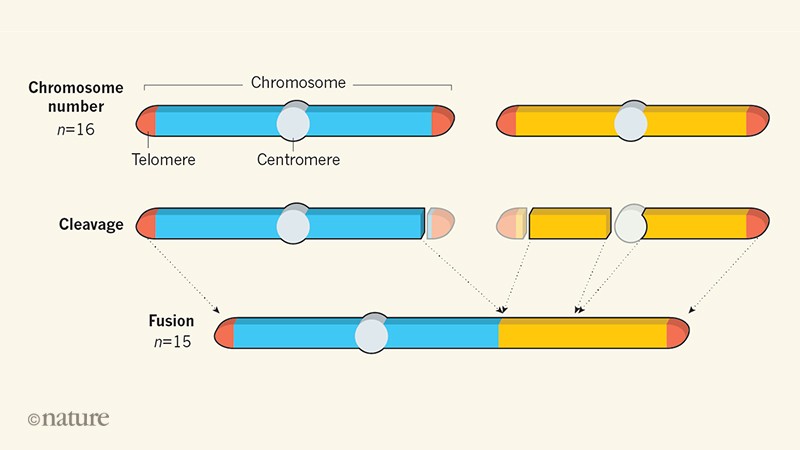

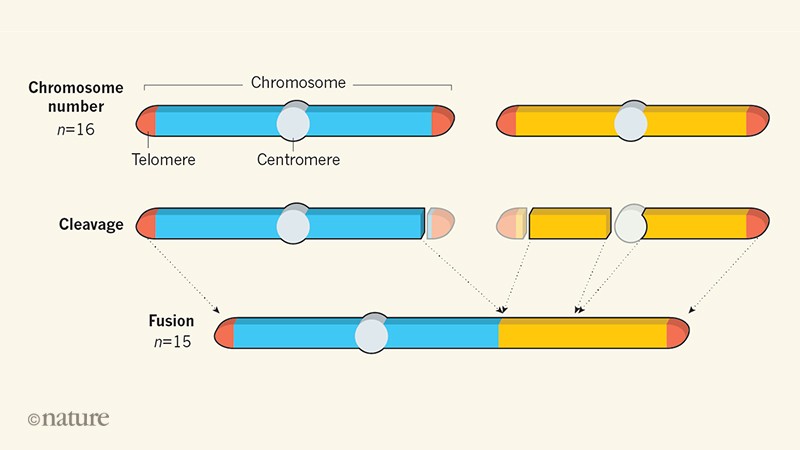

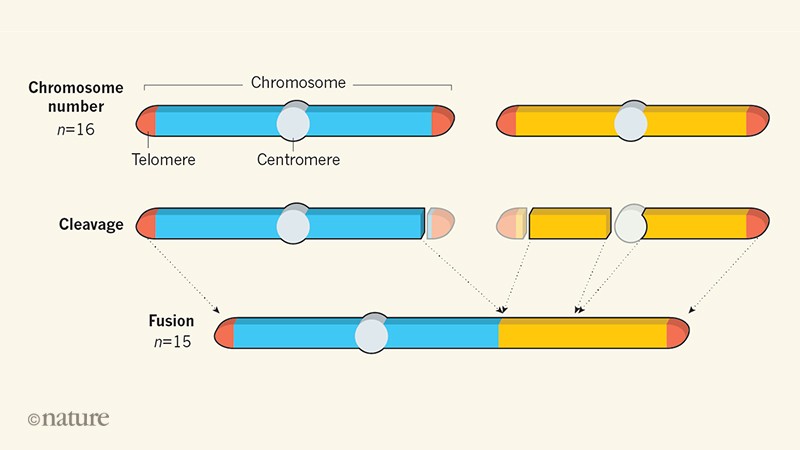

Extant species have wildly different numbers of chromosomes, even among taxa with relatively similar genome sizes (for example, insects)1,2. This is likely to reflect accidents of genome history, such as telomere–telomere fusions and genome duplication events3,4,5. Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, whereas other apes have 24. One human chromosome is a fusion product of the ancestral state6. This raises the question: how well can species tolerate a change in chromosome numbers without substantial changes to genome content? Many tools are used in chromosome engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae7,8,9,10, but CRISPR–Cas9-mediated genome editing facilitates the most aggressive engineering strategies. Here we successfully fused yeast chromosomes using CRISPR–Cas9, generating a near-isogenic series of strains with progressively fewer chromosomes ranging from sixteen to two. A strain carrying only two chromosomes of about six megabases each exhibited modest transcriptomic changes and grew without major defects. When we crossed a sixteen-chromosome strain with strains with fewer chromosomes, we noted two trends. As the number of chromosomes dropped below sixteen, spore viability decreased markedly, reaching less than 10% for twelve chromosomes. As the number of chromosomes decreased further, yeast sporulation was arrested: a cross between a sixteen-chromosome strain and an eight-chromosome strain showed greatly reduced full tetrad formation and less than 1% sporulation, from which no viable spores could be recovered. However, homotypic crosses between pairs of strains with eight, four or two chromosomes produced excellent sporulation and spore viability. These results indicate that eight chromosome–chromosome fusion events suffice to isolate strains reproductively. Overall, budding yeast tolerates a reduction in chromosome number unexpectedly well, providing a striking example of the robustness of genomes to change.

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios (Atom)